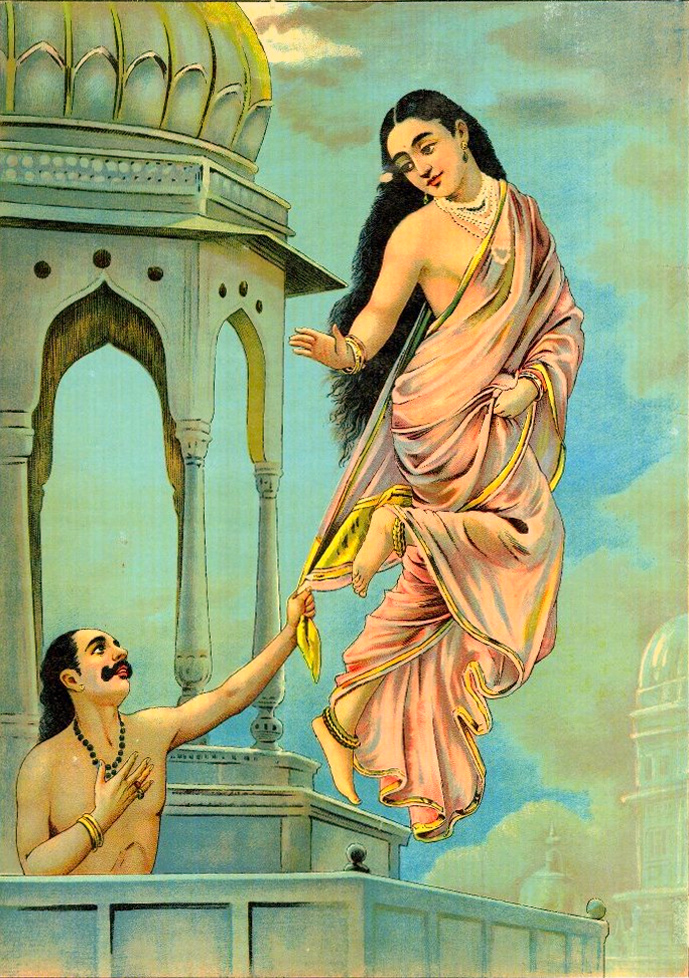

(Image: Raja Ravi Varma: Wikimedia Commons)

Is it wrong to want to buy gold ornaments for our daughters? Is it wrong to want a bigger house? Is it okay to buy a fancy new car?

Ah, Desire! Always present, never satisfied, seemingly within our grasp, but always elusive.

Like fire, the Gita says, desire only grows fiercer when it is fed. So the idea that once we achieve the right position, status, or economic level, or we possess the right car, house, family, then we will finally be happy is completely and utterly false. We see proof of that all around us on a daily basis, especially among the suicidal rich and famous, who despite having all of the above, are unhappy enough to take their own lives. And yet, unsympathetic, we condemn them for their folly, thinking what could have been if only we were given the same opportunities.

But what is so bad about desire? Isn’t it important to want something in order to act? If we were all in a desire-less state how would the world even function? A good question. If we look at the root cause of all action, good or bad, we find desire. We work because we desire money. We create families because we desire love and affection and stability. We acquire property because we desire comfort and luxury. We struggle to climb the social ladder because we want status and dignity. So if we didn’t desire any of these things what would happen? Why would anyone bother to work or even get an education? Wouldn’t the social fabric fall apart?

The Gita cautions us though, not to confuse duty with desire. Once we are born into the world, we have specific duties at each stage of our lives. Ideally, in our youth we study and learn, as adults we work and build a family, as we approach middle age, we begin to hand over the reins to the next generation, focusing on social service, and sharing our knowledge and wisdom, and as elders, we withdraw into a life of reflection and meditation. None of this comes under desire according to the Gita, but under our obligation as human beings living in the world.

This theoretical debate is all well and good but how are we to apply this in our daily lives? We decided that based on the Gita, desire is dangerous because it leads to disappointment, which leads to anger, which leads to sorrow, all of which lead us from a state of balance to one of misery.

I was trying to think of a time when I let desire get the better of me. In the past, it has been all about the job. That elusive position at a dream university. I applied, year after year, hoping. I was rejected year after year. My desire kept me coming back for more. Until one year, though I submitted my application routinely, not really expecting a response, I got one. A phone interview. I aced it. An on campus interview. It went well. By this time, desire had wrapped its tentacles around my heart, gripped me tightly in its embrace, until all I could think, speak and dream of was that offer. The days went by and nothing mattered but for the phone to ring. It didn’t. A week, two weeks, I kept myself going by imagining the delays in the hiring process, the need to check references, the busy schedules of the search committee. As long as I didn’t get a regret, there was hope. I didn’t know the letter had been sent to the wrong address. Until I finally got the call. My heart pounding, sure that the only reason they would call was to make the offer, I was told it was a follow up to the regret letter. A fittingly cruel end to a miserable three weeks. Looking back, it seems it is best to avoid desire all together, squelch it at the very outset when it raises its sly head.

Easier said than done.

Coming back to the question of whether it is wrong to want to buy things for our children or get a bigger house or enjoy our new cars, perhaps as long as we are able to keep our balance if any of those wishes are unfulfilled, then we are safe. It is only if we think we simply can’t live without any of those things, that the world will stop if we don’t buy that house or drive that car, that we are entering dangerous territory. Of course this is a slippery slope.

While most desires seem innocent enough at first, and easily relinquished, what the Gita is warning us about is how quickly what was once a whim can become a burning necessity and the cause of much agony.

Still, as householders living in a highly materialistic status-conscious society, we have to start somewhere. Precarious as it may be, this is our current position, to entertain desires without being consumed by them. We’ll have to see how successful we are.